History and Ethnic Relations

Emergence of the Nation. Though the Republic of Indonesia is only fifty years old, Indonesian societies have a long history during which local and wider cultures were formed.

About 200 C.E. , small states that were deeply influenced by Indian civilization began to develop in Southeast Asia, primarily at estuaries of major rivers. The next five hundred to one thousand years saw great states arise with magnificent architecture. Hinduism and Buddhism, writing systems, notions of divine kingship, and legal systems from India were adapted to local scenes. Sanskrit terms entered many of the languages of Indonesia. Hinduism influenced cultures throughout Southeast Asia, but only one people are Hindu, the Balinese.

Indianized states declined about 1400 C.E. with the arrival of Muslim traders and teachers from India, Yemen, and Persia, and then Europeans from Portugal, Spain, Holland, and Britain. All came to join the great trade with India and China. Over the next two centuries local princedoms traded, allied, and fought with Europeans, and the Dutch East India Company became a small state engaging in local battles and alliances to secure trade. The Dutch East India Company was powerful until 1799 when the company went bankrupt. In the nineteenth century the Dutch formed the Netherlands Indies government, which developed alliances with rulers in the archipelago. Only at the beginning of the twentieth century did the Netherlands Indies government extend its authority by military means to all of present Indonesia.

Sporadic nineteenth century revolts against Dutch practices occurred mainly in Java, but it was in the early twentieth century that Indonesian intellectual and religious leaders began to seek national independence. In 1942 the Japanese occupied the Indies, defeating the colonial army and imprisoning the Dutch under harsh conditions.

On 17 August 1945, following Japan's defeat in World War II, Indonesian nationalists led by Sukarno and Mohammad Hatta declared Indonesian independence. The Dutch did not accept and for five years fought the new republic, mainly in Java. Indonesian independence was established in 1950.

National Identity. Indonesia's size and ethnic diversity has made national identity problematic and debated. Identity is defined at many levels: by Indonesian citizenship; by recognition of the flag, national anthem, and certain other songs; by recognition of national holidays; and by education about Indonesia's history and the Five Principles on which the nation is based. Much of this is instilled through the schools and the media, both of which have been closely regulated by the government during most of the years of independence. The nation's history has been focused upon resistance to colonialism and communism by national heroes and leaders who are enshrined in street names. Glories of past civilizations are recognized, though archaeological remains are mainly of Javanese principalities.

Ethnic Relations. Ethnic relations in the archipelago have long been a concern. Indonesian leaders recognized the possibility of ethnic and regional separatism from the beginning of the republic. War was waged by the central government against separatism in Aceh, other parts of Sumatra, and Sulawesi in the 1950s and early 1960s, and the nation was held together by military force.

The relationships between native Indonesians and overseas Chinese have been greatly influenced by Dutch and Indonesian government policies. The Chinese number about four to six million, or 3 percent of the population, but are said to control as much as 60 percent of the nation's wealth. The Chinese traded and resided in the islands for centuries, but in the nineteenth century the Dutch brought in many more of them to work on plantations or in mines. The Dutch also established a social, economic, and legal stratification system that separated Europeans, foreign Asiatics and Indo-Europeans, and Native Indonesians, partly to protect native Indonesians so that their land could not be lost to outsiders. The Chinese had little incentive to assimilate to local societies, which in turn had no interest in accepting them.

Even naturalized Chinese citizens faced restrictive regulations, despite cozy business relationships between Chinese leaders and Indonesian officers and bureaucrats. Periodic violence directed toward Chinese persons and property also occurred. In the colonial social system, mixed marriages between Chinese men and indigenous women produced half-castes ( peranakan ), who had their own organizations, dress, and art forms, and even newspapers. The same was true for people of mixed Indonesian-European descent (called Indos, for short).

Ethnolinguistic groups reside mainly in defined areas where most people share much of the same culture and language, especially in rural areas. Exceptions are found along borders between groups, in places where other groups have moved in voluntarily or as part of transmigration programs, and in cities. Such areas are few in Java, for example, but more common in parts of Sumatra.

Religious and ethnic differences may be related. Indonesia has the largest Muslim population of any country in the world, and many ethnic groups are exclusively Muslim. Dutch policy allowed proselytization by Protestants and Catholics among separate groups who followed traditional religions; thus today many ethnic groups are exclusively Protestant or Roman Catholic. They are heavily represented among upriver or upland peoples in North Sumatra, Kalimantan, Sulawesi, Maluku, and the eastern Lesser Sundas, though many Christians are also found in Java and among the Chinese. Tensions arise when groups of one religion migrate to a place with a different established religion. Political and economic power becomes linked to both ethnicity and religion as groups favor their own kinsmen and ethnic mates for jobs and other benefits.

Urbanism, Architecture, and the Use of Space

Javanese princes long used monuments and architecture to magnify their glory, provide a physical focus for their earthly kingdoms, and link themselves to the supernatural. In the seventeenth through nineteenth centuries the Dutch reinforced the position of indigenous princes through whom they ruled by building them stately palaces. Palace architecture over time combined Hindu, Muslim, indigenous, and European elements and symbols in varying degrees depending upon the local situation, which can still be seen in palaces at Yogyakarta and Surakarta in Java or in Medan, North Sumatra.

Dutch colonial architecture combined Roman imperial elements with adaptations to tropical weather and indigenous architecture. The Dutch fort and early buildings of Jakarta have been restored. Under President Sukarno a series of statues were built around Jakarta, mainly glorifying the people; later, the National Monument, the Liberation of West Irian (Papua) Monument, and the great Istiqlal Mosque were erected to express the link to a Hindu past, the culmination of Indonesia's independence, and the place of Islam in the nation. Statues to national heroes are found in regional cities.

Residential architecture for different urban socioeconomic groups was built on models developed by the colonial government and used throughout the Indies. It combined Dutch elements (highpitched tile roofs) with porches, open kitchens, and servants quarters suited to the climate and social system. Wood predominated in early urban architecture, but stone became dominant by the twentieth century. Older residential areas in Jakarta, such as Menteng near Hotel Indonesia, reflect urban architecture that developed in the 1920s and 1930s. After 1950, new residential areas continued to develop to the south of the city, many with elaborate homes and shopping centers.

The majority of people in many cities live in small stone and wood or bamboo homes in crowded urban villages or compounds with poor access to clean water and adequate waste disposal. Houses are often tightly squeezed together, particularly in Java's large cities. Cities that have less pressure from rural migrants, such as Padang in West Sumatra and Manado in North Sulawesi, have been able to better manage their growth.

Traditional houses, which are built in a single style according to customary canons of particular ethnic groups, have been markers of ethnicity. Such houses exist in varying degrees of purity in rural areas, and some aspects of them are used in such urban architecture as government buildings, banks, markets and homes.

Traditional houses in many rural villages are declining in numbers. The Dutch and Indonesian governments encouraged people to build "modern" houses, rectangular structures with windows. In some rural areas, however, such as West Sumatra, restored or new traditional houses are built by successful urban migrants to display their success. In other rural areas people display status by building modern houses of stone and tile, with precious glass windows. In the cities, old colonial homes are renovated by prosperous owners who put newer contemporary-style fronts on the houses. The roman columns favored in Dutch public buildings are now popular for private homes.

Food and Economy

Food in Daily Life. Indonesian cuisine reflects regional, ethnic, Chinese, Middle Eastern, Indian, and Western influences, and daily food quality, quantity,

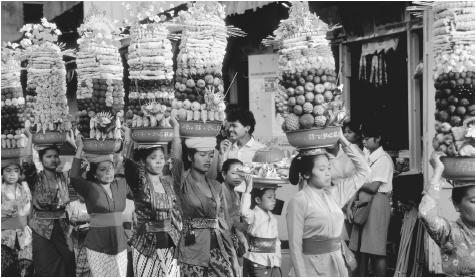

Women carry towering baskets of fruit on their heads for a temple festival in Bali.

Indonesia is an island nation, but fish plays a relatively small part in the diets of the many people who live in the mountainous interiors, though improved transportation makes more salted fish available to them. Refrigeration is still rare, daily markets predominate, and the availability of food may depend primarily upon local produce. Indonesia is rich in tropical fruit, but many areas have few fruit trees and little capacity for timely transportation of fruit. Cities provide the greatest variety of food and types of markets, including modern supermarkets; rural areas much less so. In cities, prosperous people have access to great variety while the poor have very limited diets, with rice predominant and meat uncommon. Some poor rural regions experience what people call "ordinary hunger" each year before the corn and rice harvest.

Food Customs at Ceremonial Occasions. The most striking ceremonial occasion is the Muslim month of fasting, Ramadan. Even less-observant Muslims fast seriously from sunup to sundown despite the tropical heat. Each night during Ramadan, fine celebratory meals are held. The month ends with Idul Fitri, a national holiday when family, friends, neighbors, and work associates visit each other's homes to share food treats (including visits by non-Muslims to Muslim homes).

In traditional ritual, special food is served to the spirits or the deceased and eaten by the participants. The ubiquitous Javanese ritual, selamatan , is marked by a meal between the celebrants and is held at all sorts of events, from life-cycle rituals to the blessing of new things entering a village. Life-cycle events, particularly marriages and funerals, are the main occasions for ceremonies in both rural and urban areas, and each has religious and secular aspects. Elaborate food service and symbolism are features of such events, but the content varies greatly in different ethnic groups. Among the Meto of Timor, for example, such events must have meat and rice ( sisi-maka' ), with men cooking the former and women the latter. Elaborate funerals involve drinking a mixture of pork fat and blood that is not part of the daily diet and that may be unappetizing to many participants who nonetheless follow tradition. At such events, Muslim guests are fed at separate kitchens and tables.

In most parts of Indonesia the ability to serve an elaborate meal to many guests is a mark of hospitality, capability, resources, and status of family or clan whether for a highland Toraja buffalo sacrifice at a funeral or for a Javanese marriage reception in a five-star hotel in Jakarta. Among some peoples, such as the Batak and Toraja, portions of animals slaughtered for such events are important gifts for those who attend, and the part of the animal that is selected symbolically marks the status of the recipient.

Basic Economy. About 60 percent of the population are farmers who produce subsistence and market-oriented crops such as rice, vegetables, fruit, tea, coffee, sugar, and spices. Large plantations are devoted to oil palm, rubber, sugar, and sisel for domestic use and export, though in some areas rubber trees are owned and tapped by farmers. Common farm animals are cattle, water buffalo, horses, chickens, and, in non-Muslim areas, pigs. Both freshwater and ocean fishing are important to village and national economies. Timber and processed wood, especially in Kalimantan and Sumatra, are important for both domestic consumption and export, while oil, natural gas, tin, copper, aluminum, and gold are exploited mainly for export. In colonial times, Indonesia was characterized as having a "dual economy." One part was oriented to agriculture and small crafts for domestic consumption and was largely conducted by native Indonesians; the other part was export-oriented plantation agriculture and mining (and the service industries supporting them), and was dominated by the Dutch and other Europeans and by the Chinese. Though Indonesians are now important in both aspects of the economy and the Dutch/European role is no longer so direct, many features of that dual economy remain, and along with it are continuing ethnic and social dissatisfactions that arise from it.

One important aspect of change during Suharto's "New Order" regime (1968–1998) was the rapid urbanization and industrial production on Java, where the production of goods for domestic use and export expanded greatly. The previous imbalance in production between Java and the Outer Islands is changing, and the island now plays an economic role in the nation more in proportion to its population. Though economic development between 1968 and 1997 aided most people, the disparity between rich and poor and between urban and rural areas widened, again particularly on Java. The severe economic downturn in the nation and the region after 1997, and the political instability with the fall of Suharto, drastically reduced foreign investment in Indonesia, and the lower and middle classes, particularly in the cities, suffered most from this recession.

Land Tenure and Property. The colonial government recognized traditional rights of indigenous peoples to land and property and established semicodified "customary law" to this end. In many areas of Indonesia longstanding rights to land are held by groups such as clans, communities, or kin groups. Individuals and families use but do not own land. Boundaries of communally held land may be fluid, and conflicts over usage are usually settled by village authorities, though some disputes may reach government officials or courts. In cities and some rural areas of Java, European law of ownership was established. Since Indonesian independence various sorts of "land reform" have been called for and have met political resistance. During Suharto's regime, powerful economic and political groups and individuals obtained land by quasi-legal means and through some force in the name of "development," but serving their monied interest in land for timber, agro-business, and animal husbandry; business locations, hotels, and resorts; and residential and factory expansion. Such land was often obtained with minimal compensation to previous owners or occupants who had little legal recourse. The same was done by government and public corporations for large-scale projects such as dams and reservoirs, industrial parks, and highways. Particularly vulnerable were remote peoples (and animals) in forested areas where timber export concessions were granted to powerful individuals.

Commercial Activities. For centuries, commerce has been conducted between the many islands and beyond the present national borders by traders for various local and foreign ethnic groups. Some indigenous peoples such as the Minangkabau, Bugis, and Makassarese are well-known traders, as are the Chinese. Bugis sailing ships, which are built entirely by hand and range in size from 30 to 150 tons (27 to 136 metric tons), still carry goods to many parts of the nation. Trade between lowlands and highlands and coasts and inland areas is handled by these and other small traders in complex market systems

Women carrying firewood in Flores. In Indonesia, men and women share many aspects of village agriculture.

In the nineteenth and twentieth centuries the Dutch used the Chinese to link rural farms and plantations of native Indonesians to small-town markets and these to larger towns and cities where the Chinese and Dutch controlled large commercial establishments, banks, and transportation. Thus Chinese Indonesians became a major force in the economy, controlling today an estimated 60 percent of the nation's wealth though constituting only about 4 percent of its population. Since independence, this has led to suppression of Chinese ethnicity, language, education, and ceremonies by the government and to second-class citizenship for those who choose to become Indonesian nationals. Periodic outbreaks of violence against the Chinese have occurred, particularly in Java. Muslim small traders, who felt alienated in colonial times and welcomed a change with independence, have been frustrated as New Order Indonesian business, governmental, and military elites forged alliances with the Chinese in the name of "development" and to their financial benefit.

Major Industries. Indonesia's major industries involve agro-business, resource extraction and export, construction, and tourism, but a small to medium-sized industrial sector has developed since the 1970s, especially in Java. It serves domestic demand for goods (from household glassware and toothbrushes to automobiles), and produces a wide range of licensed items for multinational companies. Agro-business and resource extraction, which still supply Indonesia with much of its foreign exchange and domestic operating funds, are primarily in the outer islands, especially Sumatra (plantations, oil, gas, and mines), Kalimantan (timber), and West Papua (mining). The industrial sector has grown in Java, particularly around Jakarta and Surabaya and some smaller cities on the north coast.

Read more: http://www.everyculture.com/Ge-It/Indonesia.html#ixzz3yWj72ZjW

silk; and batik, which alternates waxed designs with the dyeing process. Within each of these textile groups there is distinctive regional variety of technique and pattern.

silk; and batik, which alternates waxed designs with the dyeing process. Within each of these textile groups there is distinctive regional variety of technique and pattern. are known for their intricate filigree work both with jewelry and decorative models.

are known for their intricate filigree work both with jewelry and decorative models.